God's Immersion into the Life of the World

Baptism of the Lord

The Feast of the Baptism of Our Lord always falls on the first Sunday after Epiphany. The reading in Year C focuses on the transition from John to Jesus, and the omitted verses in the lectionary make that transition explicit with the arrest of John the Baptist mentioned between the preaching of John and the baptism of Jesus, now revealed as the beloved Son of God.

As the first Sunday after the Epiphany, we should expect this audible affirmation of Jesus as the beloved Son, the one in whom God is pleased. The season after Epiphany begins with the baptism and, in the Revised Common Lectionary, ends with the account of the Transfiguration. Whether he is naked in the Jordan or clothed with uncreated light on Tabor, the pseudo-season following the Feast of the Epiphany begins and ends with the voice of God declaring Jesus to be the Beloved Son. It is a season that reveals the fullness of God in the person and work of Jesus Christ.

It would be fitting to connect Jesus’ baptism with our own – a foreshadowing of his resurrection in the Gospels and our resurrection on the last day. This is central to baptismal theology. Within that same nucleus is the declaration from heaven that this is indeed the Beloved Son of God, the one anointed by the Holy Spirit. Unlike King David, there is no Samuel here to anoint his head with oil. Instead, at the Jordan, the thing that has been symbolized is manifest in reality with the Spirit of God resting on the Body of the Son, and the officiant is God the Father. We continue this practice of baptism as a participation in Jesus’ own baptism; in the waters of Baptism, he has made a way for human flesh to be born anew, from above, and anointed with the Holy Spirit by the Father who calls us beloved children. In both of these cases – adoption as God’s children and resurrection in Christ – Christ drawing humanity into the divine life.

But there is another movement in this reading, commemorated by this annual feast, and it is, I think, more appropriate to the flow of our liturgical calendar. We have just emerged from the Christmas season, beginning with the celebration of the Feast of the Nativity (Christmas Day). This feast, along with its twelve days, speaks to God’s movement toward us – the “downward” mobility of God. This is what St. Paul speaks of in the famous Philippians 2 hymn – the kenotic movement of God. It is what St. John speaks of in his first epistle, correctly identifying the source of our own movement toward God: it does not begin with us; rather, “We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19).

In his short, accessible book Being Christian, Rowan Williams says:

“To be baptized is to recover the humanity God first intended. What did God intend? He intended that human beings should grow into such love for him and confidence in him that they could rightly be called God’s sons and daughters. Human beings have let go of that identity, abandoned it, forgotten it, or corrupted it. And when Jesus arrives on the scene, he restores humanity to where it should be. But that in itself means that Jesus, as he restores humanity “from within” (so to speak), has to come down into the chaos of our human world. Jesus has to come down fully to our level, to where things are shapeless and meaningless, in a state of vulnerability and unprotectedness, if real humanity is to come to birth (3-4).”

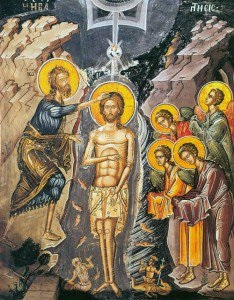

For Williams, the baptism of Jesus shows God’s solidarity with humanity. From this angle (and there are many angles besides this one), the baptism is less about revealing the divinity of Jesus than it is about revealing God as truly human. Williams goes on to say that early icons of the baptism had Jesus standing in the river Jordan, and in the waters of the river you could see the ancient gods and river monsters swimming around him. Jesus’s baptism is God’s immersion into the life of the world, with all of its suffering and chaos in tow.

But this also means that the Word of God in flesh will speak from within those places of suffering and chaos. It means that God rises up from the depths of our human experience rather than thundering from the clouds. (It is worth noting here, then, that Luke’s Gospel has the voice from heaven speaking directly to Jesus rather than the crowds. Some have suggested that this is because, for Luke, Jesus alone hears this declaration). The baptism, from this angle, is God declaring solidarity with creation, entering its depths and prefiguring the ways in which God will be known in the deepest places of creaturely joy and struggle.

Perhaps it is more fitting, in these latter days, to speak of God’s solidarity with creation and the promise that God will emerge beside us, out of the depths in which we find ourselves.

The poems of Rilke have helped me throughout the course of the pandemic, perhaps because Rilke’s poetry seems to insist upon the imminence of God, the scandalous intimacy of the Creator with the creatures, like one who is as close as our skin or the ground under our feet. One of his poems from The Book of Hours stood out to me as I considered this feast, and I will conclude with it here:

God, every night is like that.

Always there are some awake,

who turn, turn, and do not find you.

Don’t you hear them blindly treading the dark?

Don’t you hear them crying out

as they go farther and farther down?

Surely you hear them weep; for they are weeping.

I seek you, because they are passing

right by my door. Whom should I turn to,

if not the one whose darkness

is darker than night, the only one

who keeps vigil with no candle,

and is not afraid –

the deep one, whose being I trust,

for it breaks through the earth into trees

and rises,

when I bow my head,

faint as a fragrance

from the soil.

II, 3