Reckoning

Christ the King Sunday (Twenty-sixth Sunday after Pentecost)

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more…

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

Wendell Berry, “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front”

It’s easy, given the chaos of the past few years, to wonder from time to time just who the hell is in charge around here. In a world where “truth” about everything from pandemics to politics is cobbled together like a mobile meth lab and sold cheap to the bored, angry, and gullible, it’s no longer a surprise when suburban parents scream threats of violence at school board members over whether their kids should have to wear a mask or be vaccinated, or when a white male member of Congress posts a cartoon image of himself killing one of his colleagues from across the aisle – a woman of color, no less – and then tells us we just need to relax. We live at the unlikely convergence of ostensibly opposite extremes, where those who aspire to amoral autocracy meet – and embrace – an increasingly gullible throng of ersatz would-be anarchists who reject all authority except the authority that makes possible their rejection of all other authority.

We should be thankful, then, that on the last Sunday of the liturgical year, when we celebrate the now-and-coming reign of Christ the King, we’ve been given a collection of readings that help us separate the wheat of God’s peaceable reign from the chaff of every pretender to the throne. Each reading gives an account of the reign of God standing in judgment and demanding a reckoning of those kingdoms, powers, rulers, and authorities who would attempt to usurp or oppose God’s reign of shalōm.

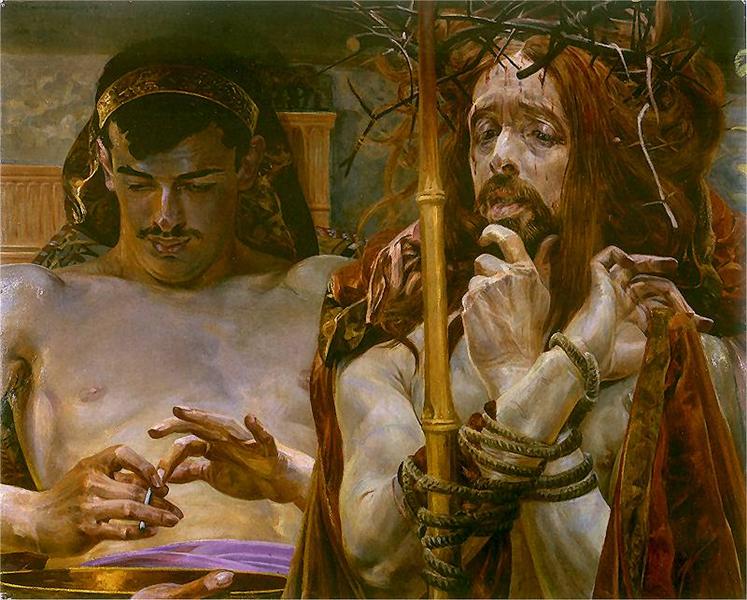

Although the first reading, from Daniel, offers the most vivid account of this reckoning, it and the other texts are animated by the gospel text, from John 18. The Temple authorities have arrested Jesus and brought him to the father-in law of the high priest, Annas, and then to the high priest Caiaphas, both of whom have interrogated him before handing him over to the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate. The conversation begins with Pilate’s question, which sums up the Temple authorities’ charges: “Are you the King of the Jews?” To which Jesus eventually responds that his kingdom “is not from this world” (ouk estin ek tou kosmou).

The word translated “world” here (kosmou/kosmos) refers not to this world in the geospatial sense – the earth – but to an organized way of thinking, speaking, and acting – a “system” characterized by self-interestedness and coercive violence (e.g., see Matthew 20:25-28). Jesus’s claim that his kingdom “is not from this world” says not so much that he reigns over another, transcendent dimension, but over this one, according to a logic born of God, one so different from the kingdoms of this world that those accustomed to those kingdoms don’t understand or even recognize Jesus’s reign as a kingdom. And yet Jesus insists that despite its strangeness to this world, his reign bears and declares the truth about creation and its Creator’s intentions for it. This, he is saying, is how things really are; we are made for love, generosity, forgiveness, and reconciliation, and not for the selfishness, suspicion, exploitation, and violence that characterize the kingdoms of this world.

That God demands a reckoning of the powers and authorities does not necessarily mean that we are called to be the agents of that reckoning, especially not by way of violence. The readings from Daniel and (less explicitly) Revelation remind us that this is God’s work, not ours. The Daniel text (7:9-14) concerns Daniel’s vision, which is described in the previous paragraph (vv. 1-8), where Daniel dreams of “four beasts… different from each other” emerging from the sea, which in Jewish apocalypticism represents the element of Creation that most stubbornly resists God’s reign. If we read further along in the chapter, we learn that the beasts represent four kingdoms which have risen and fallen in succession, each ruling, more or less oppressively, over the Jewish people.

Scholars of the text tell us that although the book of Daniel is set during the Babylonian exile, it was most likely written more than 300 years later, during the Maccabean rebellion against the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. By these scholars’ logic, the four kingdoms represented by the beats are the Babylonian, Median, Persian, and Greek empires, respectively. The focus of Daniel’s vision is the fourth beast, which is terrifying and destructive and “different from all the rest.” Daniel attends particularly to this beast’s ten horns, which probably represent the Seleucid kings who serially succeeded Alexander the Great, and then to another, smaller horn, one with “human eyes and a mouth speaking arrogantly.” This horn likely represents Antiochus IV, the megalomaniacal Seleucid ruler whose aggressive application of the doctrine of Hellenization and repeated blasphemous attacks on Judaism and its Temple sparked the Maccabean revolt.

What happens next, in the verses designated for lectionary reading (vv. 9-14), is for our purposes especially noteworthy. As Daniel watches, he sees the thrones of the heavenly court being set in place, with a vividly described “Ancient One” taking his throne. Then he sees the assembled court sitting in judgment, its books opened. The continued arrogant yammering of the small horn evidently draws the attention of the court, which executes its judgment; the fourth beast is put to death, and its reign quickly replaced by a new presence in the court room, one Daniel describes as “like a human being” (often translated as “son of man”). The Ancient One gives him “dominion and glory and kingship/that all peoples, nations, and languages/ should serve him/His dominion is an everlasting dominion/that shall not pass away/and his kingship is one/that shall never be destroyed.” Our Jewish brothers and sisters have historically read this “one like a human being” as representing the Jewish community, while Christians identified him from the beginning as Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah.

I’ve left one interesting detail unattended. The great temptation facing Christians, who are members of God’s reign in a world ruled by violent domination, is (and always has been) to seek to secure the peaceable reign of God by means that have no place in that reign. We have often succumbed to that temptation, and just as often been transformed by our capitulation, such that the kingdom we imagine we are defending bears little resemblance to the one proclaimed and embodied by Jesus. One reason for this is that we have harnessed ourselves to this or that worldly kingdom, sometimes even confusing those kingdoms with the reign of God. In doing so we overlook something important that our reading from Daniel gestures toward.

In the same part of the passage that describes the destruction of the fourth beast, Daniel also mentions the other three beasts. He says that “their dominion was taken away, but their lives were prolonged for a season and a time” (v. 12). Those beasts have continued to rule on earth in various guises as the several iterations of the kingdoms of this world. Some have been horrific, others less so. Still others have been comically inept. A very few have been relatively just, and even, in a limited way, forces for good. It is these that Christians should regard most warily, even or perhaps especially when they adopt our most officious language and pieties. For when they do this, we are most apt to forget that they are still beasts, destined to rule “for a season and a time” and then to pass away. They may offer their friendship, but always for a price, usually one that requires us to look away from or even to take up their manners and methods. When we do this, whatever “victories” come our way will be Pyrrhic, and the God and kingdom to whom we bear witness will be pale simulacra of the reign of the Ancient One of whom Daniel speaks.

We must remain patient, then, loving our neighbors, living peaceably with one another, and speaking truth to power, knowing that the vision of John the Revelator from the week’s third reading is, when all is said and done, true:

Look! He is coming with the clouds;

every eye will see him,

even those who pierced him;

and on his account all the tribes of the earth will wail.

When this reckoning takes place is none of our business. Our business is to embody, however partially and imperfectly, God’s reign of shalōm. How we do this is something we have to figure out on the fly. Perhaps we might find inspiration from these words, from Wendell Berry poem excerpted as the epigraph above:

So, friends, every day do something that won't compute. Love the Lord. Love the world. Work for nothing. Take all that you have and be poor. Love someone who does not deserve it… Expect the end of the world. Laugh. Laughter is immeasurable. Be joyful though you have considered all the facts… As soon as the generals and the politicos can predict the motions of your mind, lose it. Leave it as a sign to mark the false trail, the way you didn't go. Be like the fox who makes more tracks than necessary, some in the wrong direction. Practice resurrection.